Han Kang Wins 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature

South Korean Readers Frenzied in Book Hunt

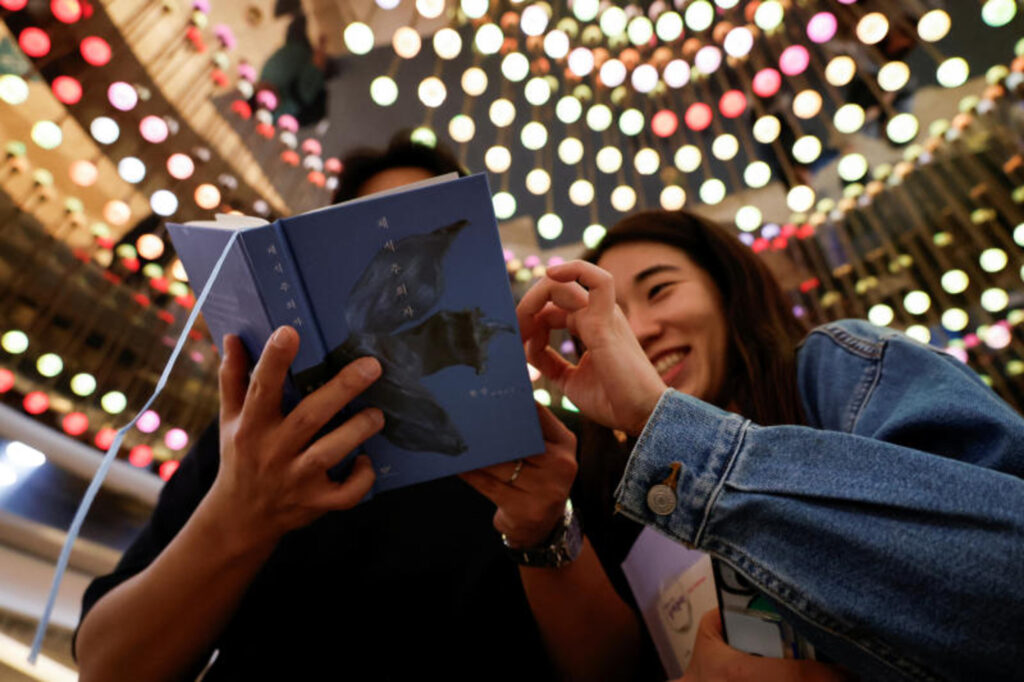

South Koreans flocked to bookstores on Friday, October 11, crashing websites in a frenzy to buy the works of Han Kang, who unexpectedly won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature. Yet, even with the world clamoring for her words, Han has remained absent from the public eye.

Kyobo Book Centre, the largest bookstore chain in South Korea, reported that sales of Han Kang’s books skyrocketed. Shelves emptied as quickly as they were restocked, with the chain admitting it may not have enough copies to meet the demand.

A Historic Moment

This feverish response marks a historic moment for South Korea, as Han Kang becomes the first South Korean to ever win the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature.

“I can’t believe it. This is a rare honor for our country,” said Yoon Ki-heon, a 32-year-old man shopping at a Kyobo branch in Seoul. “South Korea has never won a Nobel before, so hearing that a writer using the Korean language has achieved this kind of global recognition is astounding.”

Within hours of the Nobel announcement on Thursday, October 10, numerous bookstore websites crashed due to the overwhelming number of visitors. As of Friday morning, nine of the top ten bestselling titles at Kyobo were by Han Kang.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Han Kang for her 2016 novel, *The Vegetarian*, originally translated into English from Korean. That same translation won the Man Booker International Prize, launching Han’s name into global literary circles.

Han’s father, Han Seung-won, a prominent writer in South Korea, told Reuters that his daughter’s international success owes much to the careful translation of her works into English. “Her writing is subtle, haunting, and full of sorrow,” he said. “The translations beautifully capture the essence of the Korean language, which may explain her international acclaim.”

Beyond “The Vegetarian”, many of Han’s works, translated into English, delve into the darkest chapters of Korean history. “Human Acts”, for instance, recounts the bloody 1980 Gwangju Uprising, during which hundreds of civilians were killed by South Korean military forces. Another significant work, “We Do Not Part”, explores the aftermath of the Jeju Island Massacre between 1948 and 1954, where an estimated one-tenth of the island’s population was brutally killed in government crackdowns.

Kim Chang-beom, head of an association representing the families of Jeju Massacre victims, expressed admiration for Han’s work. “I hope her books will bring healing to survivors and honor the memory of those lost,” he told Reuters.

Similarly, Park Gang-bae, leader of a support organization for the Gwangju Massacre victims, was moved by Han Kang’s Nobel win. “The characters in “Human Acts” are people we meet and live with every day. Her victory is a tribute to those forgotten souls,” he told Reuters.

Celebration Deferred

Despite the intense public interest in South Korea’s first Nobel laureate, Han Kang has yet to step into the spotlight. As of Friday morning, no media outlet had succeeded in interviewing her, and she has not made any public appearances. According to her father, Han feels unable to celebrate in light of ongoing global crises, particularly the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Han reportedly received news of her Nobel win only 10 to 15 minutes before the official announcement and initially believed it might be a prank.

Though Han Kang continues to avoid the media, her books are flying off the shelves. Several of her works, including “The Vegetarian”, have already been translated into Vietnamese.

Han Kang’s writing lingers in the minds of readers long after they’ve closed her books. The stories resonate not only through their arresting plots but also through the profound layers of meaning she weaves throughout her narratives.

At the core of “The Vegetarian” lies a complex interplay between societal expectations, personal trauma, and a woman’s quest for autonomy. Written with precision and emotional depth (though some nuance may be lost in translation), Han Kang tells the story of Yeong-hye, a woman who makes the radical decision to stop eating meat—not merely as a dietary change, but as a personal rebellion.

This decision triggers a psychological unraveling, affecting both Yeong-hye and those around her. What begins as a small act of defiance against societal norms soon transforms into something much deeper. Yeong-hye’s mental state begins to fracture, and her relationships crumble.

One of the novel’s greatest strengths is its exploration of the thin line between body and mind, freedom and submission. Han Kang doesn’t just tell the story of a woman refusing to eat meat; she leads readers on a journey through the oppressive weight of societal expectations, particularly those placed on women in South Korea’s patriarchal society—a structure that, while modernizing, still bears the hallmarks of its rigid past.

Elusive Liberation

Yeong-hye’s decision is both an assertion of self and a desperate attempt to escape the suffocating pressures of society and family. Yet the path to what might be considered liberation is fraught with emotional and mental isolation, leaving readers to wonder whether the character is asserting autonomy or descending into madness.

What makes Han’s novel so captivating is the way she juxtaposes Yeong-hye’s quiet, internal rebellion with the violent reactions of those around her. The novel, structured in three parts, each told by a different character, offers a multi-faceted view of Yeong-hye’s transformation, heightening the tension between her inner world and the external forces seeking to control her.

Through her sparse, symbolic prose, Han Kang allows readers to interpret Yeong-hye’s journey in myriad ways. The character’s transformation is both beautiful and terrifying—a paradoxical complexity that lingers in the reader’s mind.

On a thematic level, Han Kang’s work questions what freedom means in a society marked by strict, often invisible boundaries—especially for women. Yeong-hye’s refusal to eat meat can be seen as a metaphor for rejecting submission, while emphasizing the price one pays for defying societal norms.

In a way, Han Kang critiques a world in which women’s bodies and desires are controlled, where stepping outside the norm is met with suspicion, hostility, and even violence. The reactions of those closest to Yeong-hye, particularly her husband and family, reflect the cruelty of South Korean society—a cruelty that, in some ways, echoes across the broader East Asian context.

Han Kang doesn’t offer clear solutions. Yeong-hye’s unraveling forces readers to confront the fine line between self-assertion and madness, while asking what the cost of personal freedom truly is.

With the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, Han Kang’s “The Vegetarian” is now solidified as a cornerstone of modern literature.